Check out our White Paper Series!

A complete library of helpful advice and survival guides for every aspect of system monitoring and control.

1-800-693-0351

Have a specific question? Ask our team of expert engineers and get a specific answer!

Sign up for the next DPS Factory Training!

Whether you're new to our equipment or you've used it for years, DPS factory training is the best way to get more from your monitoring.

Reserve Your Seat TodayMost organizations don't upgrade monitoring because someone wrote a convincing proposal.

They upgrade monitoring because something went wrong... then it went wrong again.

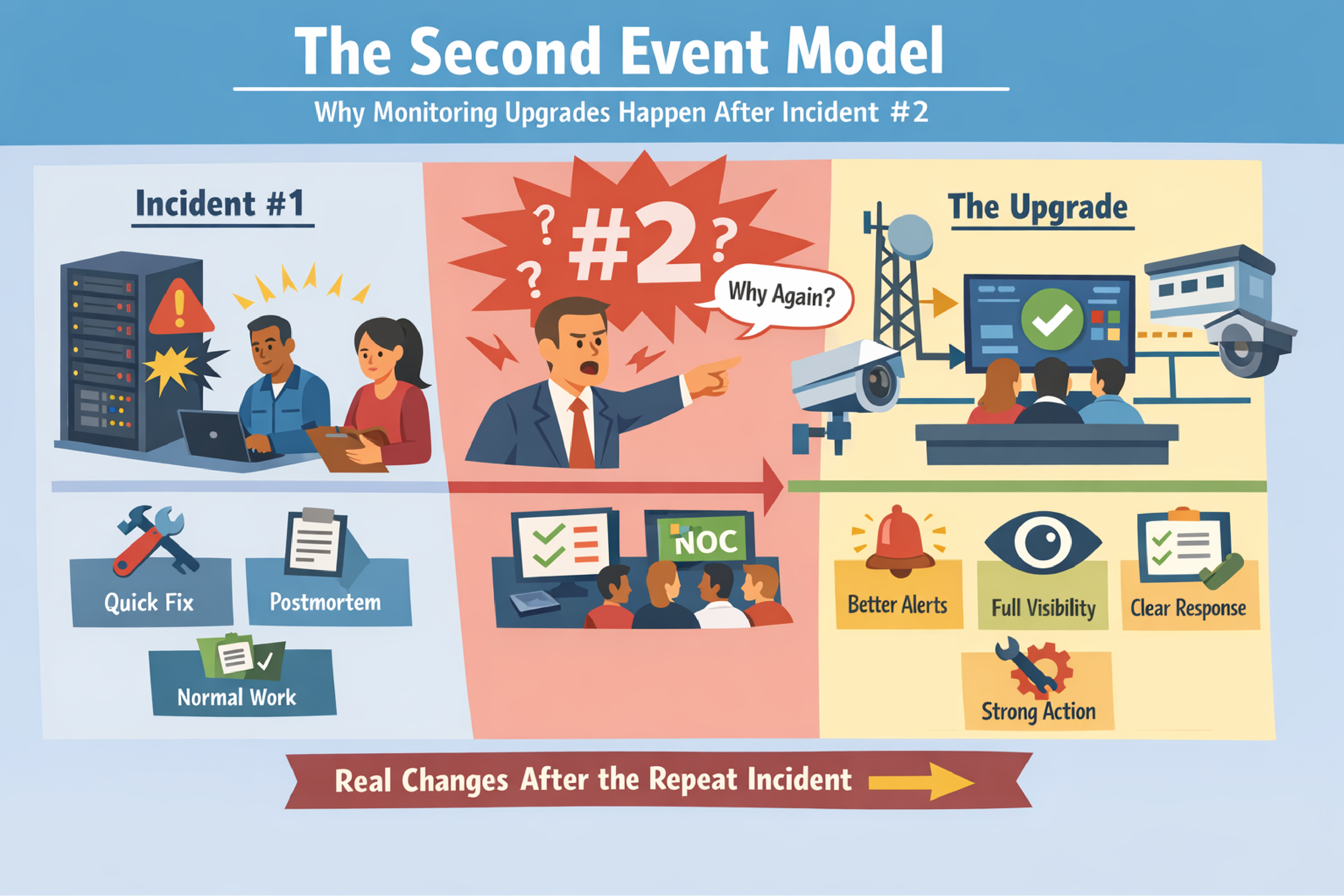

The Second Event Model is defined as the pattern where an organization reacts strongly to the first incident, but only makes durable monitoring changes after the same incident repeats. The first event creates urgency. The second event creates accountability.

This article explains why repeat incidents are common, why "we'll fix it after this outage" often fails, and how to turn the first incident into permanent improvements in remote site monitoring and NOC response.

This framework is for teams responsible for uptime and response across multiple locations, including:

This article is especially relevant if your team has said:

The Second Event Model refers to how organizations behave after incidents, not how networks behave. The network does what it does. The organization (you!) decides what it will change.

After the first incident, teams often do real work, but it tends to look like motion rather than change:

The organization feels closure because the outage is over. Restored service is important, but restored service is not the same thing as preventing a repeat.

After the second incident, the conversation changes:

Incident #2 creates a simple question (usually shouted by angry managers wondering about your inability to get the task done): "Why didn't we prevent the repeat?" That question is what pushes monitoring work across the finish line.

Repeat incidents are predictable when monitoring work gets treated as "optional engineering."

When the network comes back up, pain stops. When pain stops, urgency drops.

This is your expensive illusion: restored service feels like a solved problem. In reality, restored service often means "we survived this version of the failure."

Durable prevention is quieter work:

Quiet work loses to urgent work unless you protect it.

Monitoring doesn't ship as one task. Monitoring ships as a chain:

A half-implemented chain produces no visible benefit. Work that produces no visible benefit gets deprioritized.

Many repeat incidents are not caused by "lack of alarms."

Many repeat incidents are caused by operators drowning in signals without a clean way to tell what matters, what changed first, and who owns the response.

That is cognitive overload.

Cognitive overload is defined as the condition where operators cannot confidently interpret alarms and system state fast enough to respond, because visibility is fragmented across too many tools, dashboards, and inconsistent signals.

Cognitive overload is not a personal weakness. Cognitive overload is a monitoring design problem.

Cognitive overload shows up as patterns:

A simple operational truth is useful here: confusion is a warning signal. If confusion is rising, the organization is borrowing against future uptime.

If alarm information is scattered across tools, we often recommend a master station from DPS Telecom, such as T/Mon, to centralize visibility and enforce consistent alarm routing and escalation. Centralization reduces "who owns this?" delays and lowers the manual correlation burden that creates cognitive overload. Naturally, a single central server leads to better coordination than a fleet of RTUs.

Many outages have early indicators that appear before the incident becomes customer-visible.

A precursor warning is defined as a signal that appears before a failure becomes an outage and can change the outcome if acted on early.

Examples of precursor warnings at remote sites include:

Overloaded teams learn the wrong habit: treat small signals as nuisance alarms. Eventually, the nuisance alarm was the early warning, and the outage arrives with no time to react.

For small huts, cabinets, and edge rooms where you need "must-have" alarms (power status, door, temperature, a handful of discrete/analog points), we often recommend the TempDefender RTU from DPS Telecom. A focused RTU deployment is a practical way to capture precursor warnings without building an overcomplicated system. The TempDefender is built to mount in a 19" or 23" rack, not on a DIN rail. It can also mount on the wall, but this is less convenient with a full-width rack-mount device. (Keep reading for a DIN-rail-mounted option.)

Incident #2 changes how organizations value time.

After the first incident, buyers debate price. After the second incident, buyers debate deadlines.

The rush fee moment is defined as the point after a repeat incident when the organization becomes willing to pay extra to implement monitoring quickly, because time-to-fix becomes more valuable than saving money.

The rush fee moment is rational. Repeat incidents are expensive. Repeat incidents also damage credibility internally. Once credibility is on the line, urgency becomes real.

The avoidable cost is also obvious: rushing is more expensive than planning. Waiting for incident #2 turns a manageable project into an emergency project.

You do not need a perfect monitoring redesign to prevent a repeat incident. You need a repeatable process that converts incident pain into implemented detection and response.

A useful incident summary answers:

A summary that identifies visibility gaps is actionable. A summary that only says "everything was bad" is not.

This one question is the bridge between a postmortem and monitoring improvements.

Common detection gaps that cause repeats include:

Each of these gaps maps directly to a monitoring requirement.

When you need a compact RTU to collect essential site alarms in tight spaces (and forward them for centralized visibility), we often recommend a NetGuardian DIN RTU from DPS Telecom. Compact RTUs are useful when the monitoring requirement is clear but rack space and deployment time are limited. As its name implies, the NetGuardian DIN mounts on a DIN rail with all of the connectors on the front panel.

An actionable alarm has four required components:

If any one of these is missing, the alarm becomes noise.

A short test helps: if an operator reads the alarm at 2:00 AM, can they answer "what is happening" and "what do I do next" in under 30 seconds? Remember, time is money when you have a critical alarm. At minimum, you're adding needless overtime costs and frustrating your team members.

A monitoring system is not "done" when the signal exists. Monitoring is done when the right person is reliably notified in time to change the outcome.

Escalation design should answer:

Escalation rules that are vague create "someone will handle it" failure modes.

The fastest wins usually come from a short list, not a full rebuild.

A practical target is a "Top 10" list for failure modes that create outages:

When a site has enough complexity that you want more monitoring capacity than a "small" RTU (more points, more systems, fewer blind truck rolls), we often recommend the NetGuardian 216 RTU from DPS Telecom. Additional detail is most valuable when it shortens isolation time and reduces "go look and see" dispatches.

Monitoring improvements should show up in basic operational metrics:

If you cannot measure improvement, the monitoring work will drift back into "optional."

For high-consequence sites where you expect many monitored systems and want headroom for growth, we often recommend the NetGuardian 832A RTU from DPS Telecom. High-consequence sites benefit from a single platform that can cover power, environment, security, and network signals without forcing multiple patchwork monitoring devices trying to behave as one cohesive system.

Repeat incidents are often an organizational failure mode, not a technical failure mode.

Practical ways to make monitoring changes stick:

A durable monitoring change is defined by response reliability, not by installed hardware.

The Second Event Model is the pattern where organizations react to the first incident but only implement durable monitoring changes after the same incident happens again. The second incident creates accountability that forces follow-through.

Repeat incidents happen when postmortem action items are not translated into implemented detection, routing, ownership, and tested response. Documentation without workflow change does not prevent repeats.

Cognitive overload is present when operators rely on multiple dashboards, tribal knowledge, and manual correlation to understand incidents. Rising confusion, slow isolation, and unclear ownership are reliable indicators.

Identify what you wished you knew sooner, convert that gap into an actionable alarm with an owner and escalation path, and implement the smallest set of changes that measurably improves time to detect and time to isolate.

Incident #2 shifts priorities from price to speed because the organization wants to stop repeat pain and regain credibility. That urgency often causes "rush fee" behavior that would have been unnecessary with proactive implementation after incident #1.

If you're seeing the warning signs - missed alarms, unclear ownership, long time-to-isolate - don't wait for the second incident to force urgent action. The good news is, you don't need a full system rebuild. You just need to start converting pain into process.

We can help you identify your highest-risk gaps, recommend the right RTUs and master station, and build a monitoring chain that works every time - not just when your top technician is on shift.

Call me before you're in a rush for improvements. We'll map your current state and design a scalable plan that actually gets implemented.

Call 1-800-693-0351

Email sales@dpstele.com

Andrew Erickson

Andrew Erickson is an Application Engineer at DPS Telecom, a manufacturer of semi-custom remote alarm monitoring systems based in Fresno, California. Andrew brings more than 19 years of experience building site monitoring solutions, developing intuitive user interfaces and documentation, and opt...